From Larchmont to Beachmont

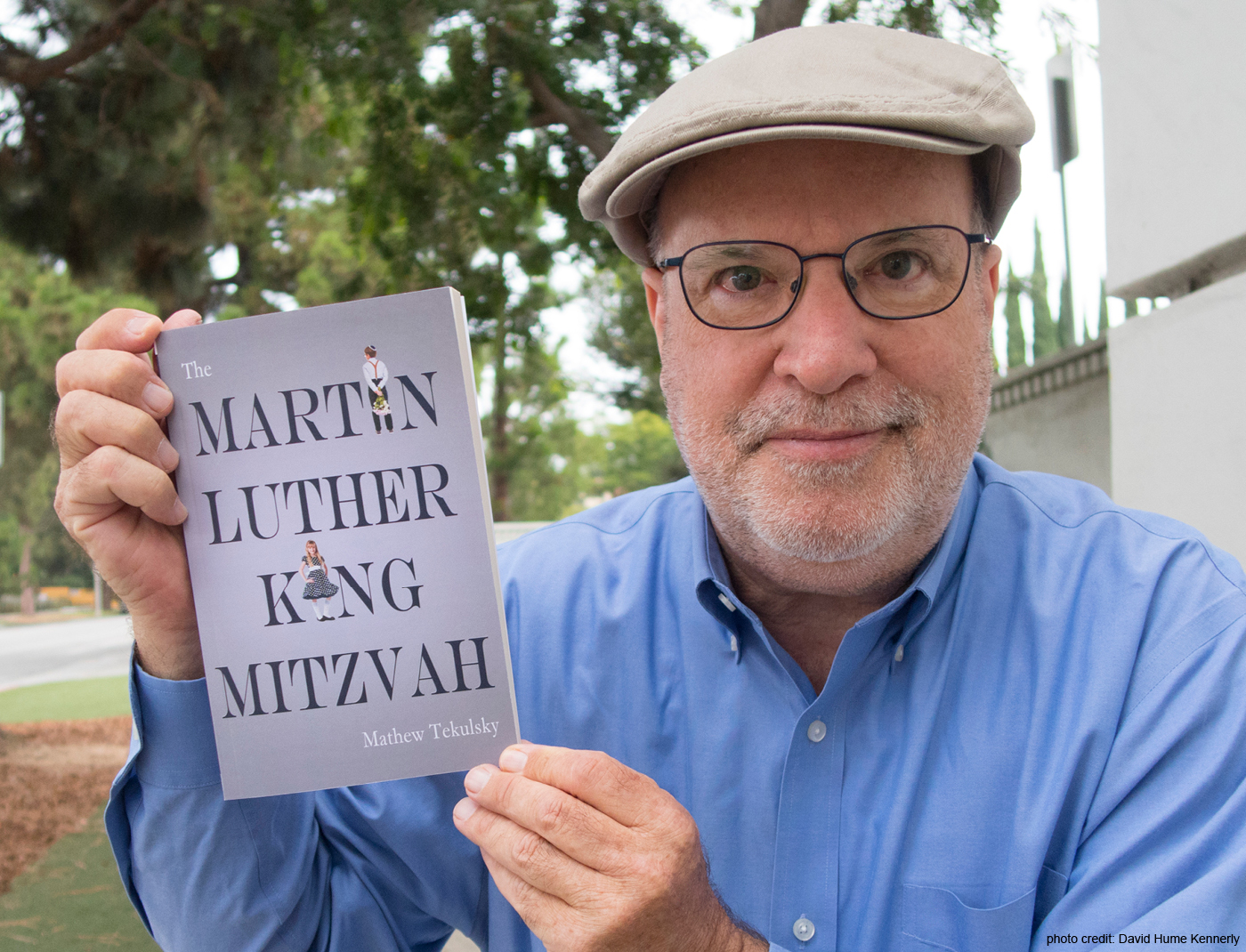

BEHIND THE SCENES WITH THE MARTIN LUTHER KING MITZVAH

Each of us has a hometown deep within us, deep within our childhood. My hometown is Larchmont, New York, a tree-lined suburb of New York City, where I grew up from being born in 1954 until I got out of college in 1975. My early years in Larchmont fill me with wondrous memories of a skating pond, of sledding down hills at the local golf course, of playing hockey when the ice froze over on the creek down the street from my house; winter memories of white drifts of snow and shoveling the neighbors’ driveways and front walks until my pockets were filled with dollar bills.

Living by the Long Island Sound, I played on the rocks on the shoreline and made up animals and other objects that the rock shapes became; a whale, a pig, a toaster. Halloween brought in bags of Baby Ruths and Three Musketeers; the chestnut pods fell from the trees and I opened the pods up to reveal the shiny brown nuts inside, never to eat them, just to marvel at their beauty. Maple trees lined our streets in the Larchmont Manor, along with elms, beeches, walnuts, oaks; and the streets were named after these trees. I lived on Hazel Lane, my backyard catty-corner from the backyard of a great author, Phyllis McGinley, who lived over on Beach Avenue. I walked by her grand farmhouse, set back by a long lawn, and wondered what stories she was creating inside that place. I must have been nine years old, in fourth grade, when I decided to become a writer like Phyllis McGinley. I had never seen any of her books, never saw her in the yard or anywhere else, just knew she lived in that big house. That’s what I want to do, I thought.

So how does the creative process occur? Fifty-two years later, I decided to write a novel. I had published my share of nonfiction books about butterfly gardening, hummingbird gardening, how to photograph birds, even a best-selling cookbook of coffee drinks. But my first love was the short story, and although I had some of my short stories published in some literary magazines in 1984 or so (I vowed before my thirtieth birthday I would have short stories published), I had never attained the literary success that I had envisioned for myself even in those early years of walking past Phyllis McGinley’s house. Now, McGinley won the Pulitzer Prize for her poetry, and she was also a popular children’s book author and essayist. I was searching for such grand things, along the lines of Hemingway and Steinbeck. Many rejections of my first attempts at novels in the 1980s cowered me into the nonfiction world, where I was happy enough to carve out a nature- writing niche for myself.

But deep inside my creative soul there was a massive hole. I had to fill it with a story of some kind that would resonate with the public, and embody in my writing style the spirit of the masters whom I emulated so much. Finally, I hit on an idea. I would try to capture in words the experience of growing up in a small town like Larchmont in the 1960s, somehow populate the book with interesting characters, and by hook or by crook, develop a plot that readers would find interesting.

But where to begin? I remembered in high school being bullied by this young hoodlum. He had it out for me for some reason and I spent a lot of time hiding out from this guy, not wanting to have my face pounded in or to break my hand hitting him. Years later, I vowed that if I ever ran across this guy and I had a gun handy, I’d blow his head off. But how to channel that energy into a story? OK, let’s do a story of revenge. That’s it. He runs across this guy years later and…slits his throat, strangles him, what? No, better yet, what if they were kids. That’s it, they’re kids, but not in high school, how about in grade school, maybe in seventh grade or so, in 1966.

So why does this kid hate me so much? Maybe because I’m Jewish. We had a lot of anti-Semitism in Larchmont when I was a kid. Our neighbors even threw eggs at our house and we had to clean off the door when the egg yolks and whites hardened. These kids were Protestants whose father had even grown up with my mother, and yet his kids did this to us. I asked Dad to go to the police about it, but he decided to keep a low profile. Let’s not make any waves. Oh well. Indeed, in Larchmont at that time, we had three major beach clubs, each of which was populated by the Protestants; the Catholics; and the Jews. And never the twain should meet.

My mother used to tell us kids, “But for the grace of God go us,” meaning that the Nazis could take over the United States someday and we would have our own Hitler coming after us, right here in Larchmont. It hadn’t been that long after the War, after all. I even had nightmares of being in a concentration camp, but I’d wake up before they did anything bad to me. Well, what if I wrote about anti-Semitism in my book. That’s it, one of the kids has it out for me because I’m Jewish. But why?

Then I remembered this girl I had a crush on in fourth grade. I used to follow her home from school just to watch her sandy-blonde ponytail sway back and forth when she walked. She had the prettiest face I had ever seen and I just thought about her all day long. Of course I was too shy to say anything to her, and I never did, all through high school. She lived down the street from me and she and I took the same route home from Chatsworth Avenue School, down Beach Avenue, past Phyllis McGinley’s house. She turned up a street near mine, and I went on to my house alone. Even at nine years old, I thought this girl was perfect.

What if the bully were this girl’s older brother? That’s it. So I started writing the story, leading up to where I get my revenge. But then something happened. Instead of being a story about revenge, it became a story about redemption and the coming together of disparate people. Now, along the way, as a subplot, I worked Phyllis McGinley into the story as a blacklisted writer (although McGinley was never blacklisted), and through this writer, named Gladys McKinley in the book, our boy and girl, Adam and Sally, are taken by Gladys and her black housekeeper Honey to hear Martin Luther King’s historic “Beyond Vietnam” speech at the Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, a year to the day before he was assassinated.

Well, I was off to the races now, pulling the characters together as the political and personal aspects of the story wove themselves into a quilt of nostalgia and history. Through it all, the character of my hometown of Larchmont (called Beachmont in the novel) looms large, with its tree-lined streets and the Long Island Sound hovering nearby. What I would give to go back and relive my childhood again, and have my parents back, and just rejoice in the beauty of that time. But time moves on, like a mighty river, as Dr. King used to say, and I have to move on with it. But I still have my story to go back to, even though it’s ninety-five percent made up, and only five percent based on truth. How truthful is a novel anyway? Only as truthful as the suspension of disbelief becomes in the reader, and then you reach a greater truth, don’t you, the truth that we all live with every day, to be honest with ourselves and with others, and to try and build a better world.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Where would the characters in the book come from? Well, I just mentioned Honey, the black housekeeper, who was based on our real housekeeper Odessa King, who was like family to us. She came to our house a couple of times a week, and when I came home from grade school, she made me grilled cheese or tuna fish sandwiches while I watched “Concentration” on TV. Then I walked back to school. Honey also worked for my mother’s father across town.

His name was Leo Fish, and he is also a character in the novel, by the name of Grappa, which is what we called him in real life. Now, Larchmont is a comfortable, indeed wealthy neighborhood, and back during the Vietnam War, I’d venture that half the town was for the war and half against, or perhaps more for it than against. Regardless, in real life, my grandfather, probably in 1969 or 1970, when I was 15 or 16 years old, put a decal in the rear winder of his olive-green Mercedes sedan, and it consisted of an upside-down American flag and the words, “Save the Country, Stop the War.” Imagine Grappa driving into the parking lot of our fancy beach club, Beach Point, and all of the members seeing just what he thought about Nixon and the war. An amazing guy, with a great sense of right and wrong. He was self-made, an insurance salesman, and he brought up my mother with his same sense of a love of life and of people. We called him Grappa, and in the novel, he has the same name. He supports Adam and Sally in their perhaps naïve attempt to stop the Vietnam War by staging an anti-war protest in their own small town, Beachmont.

In real life, my maternal grandmother died when I was only four years old, and a few years later, Grappa married a Hungarian-American woman named Alice Gross. She made a great walnut torte which we had every time we went over to Grappa’s house for a holiday dinner. In the novel, I make Alice an Austrian woman from Vienna, and I call her Elise, and yes, in the book she makes the world’s greatest walnut torte.

So where did Adam’s sidekick Jimmy Robbins come from? Well, a couple of houses down from me in Larchmont, a kid lived by the name of Jimmy Stuart. No, not the actor. He spelled his name S-T-U-A-R-T. In the novel, Adam and Jimmy Robbins build a clubhouse out of reeds down by the creek, and Jimmy Stuart and I did just this when we were about twelve years old. Plus, Jimmy did sneak cigarettes from his mother’s silver cigarette case that sat on her glass coffee table in their living room, and we puffed on these things down at the clubhouse, without inhaling of course.

In real life, Jimmy did have access to some Playboy magazines, I think because his father had a subscription, but we never brought the Playboys down to the clubhouse, as we do in the novel. (As an aside, it is interesting that my editor at Fitzroy Books, Jaynie Royal, kept all of my references to the Playboys virtually as I wrote them, and thanks to the Internet, I could research who the Playmates of the Month were during the school year of 1966 to 1967, and I worked these references into the text. The question is, will young boys all over the country go to the Internet now and try to check out these Playmates, as I have referenced them in the book. This might get my book banned at a few schools, or it could create a flood of interest for the book, at least among young boys.)

So why did I decide to make Jimmy dyslexic? Well, a friend of mine from high school had dyslexic tendencies, and I just transferred this trait onto the character of Jimmy Robbins. As it happened, Jimmy Stuart didn’t stay in Larchmont through high school, and my last memory of him is from those times when we went down to our clubhouse by the creek.

The creek itself is an interesting character in the book, as is the Long Island Sound and indeed, winter itself. In real life, the creek is really an inlet from the Long Island Sound that looked like a river basically, and you could access the shoreline of this creek at the end of Guion Lane, which ran perpendicular to my house. My bedroom window looked down Guion Lane and right at the creek in the distance. It was only a block away, and in the winter we used to just walk down the street with our ice skates on already, with rubber protectors on the blades. I had my hockey stick and my puck ready for ice hockey on the creek during the dead of winter, when the creek had had enough time to freeze over. Lots of people skated on the creek, which actually had moving water beneath it—after all, it was not a pond. But we took our chances and most of the time it worked out.

Well, one day when I was in high school, I was in charge of this fourteen year-old kid who lived two houses up Kane Avenue from me. I was about sixteen I guess. We decided to walk on the ice-covered creek to Willow Park, where the basketball court was, instead of taking the street. It was only a block or two in distance, but at one point, I could feel the ice cracking beneath me and then it gave way and both me and this kid fell into the water, up to our chest or so, and fortunately we were able to walk our way through the cold water to the shore. I took this kid home as fast as I could and retreated into the warmth of my own house, embarrassed as the day was long. Nothing ever came of it, but it was one of the worst decisions I ever made to take the shortcut to the park by walking along the frozen-over creek.

Well, that incident paid dividends in THE MARTIN LUTHER KING MITZVAH when I got to the point in the hockey game where Peter Fletcher falls through the ice on the creek and…well, you’re going to have to read the book to see what happens, but the germ of that scene, probably the most important scene in the entire novel, came from a real experience I had when I was in high school, not when I was twelve years old, as the characters are in the book.

Speaking of Jimmy Stuart, there is one incident in the book based on my experiences with this kid that is absolutely true, to a point. When we were about twelve years old, Jimmy did indeed suggest that we go down to Larchmont Avenue (called Beachmont Avenue in the book) and throw snowballs at cars—but only aiming at the hubcaps. It was the dead of winter and a clear night, and the scene played out just as I described it in the book with Jimmy Robbins, except for one difference. In real life, the officers took Jimmy and I down to the police station, where we were presented to a sergeant behind a tall desk.

He towered above us and I knew my life was over because my parents were going to kill me, and then the most amazing thing happened. The sergeant gave us the coldest, meanest look he could and then he said, “Now get out of here.” You mean, he wasn’t going to tell our parents? We were free to go? Jimmy and I got up as casually as we could and we probably walked home in silence. Well, my editor thought it was too hard to believe, that the cops would scare the crap out of these two kids by hauling them down to the police station, so I softened the scene up and had the officers let the kids off the hook right on the spot. So much for truth being stranger than fiction.

Another aspect of winter that crops up in the novel are the sledding episodes at the Bonnie Glen Country Club golf course. In real life, this was the Bonnie Briar Country Club, and in the winter, we all went to a big hill on the golf course, just off the road where we parked. We climbed up this huge mountain (or so it seemed to us kids), and then we slid down the hill on our Flexible Flyers or on a toboggan. The thing of it was, there was a river at the bottom of the hill, at the end of a long flat area of snow. Now, nobody ever fell into the water, but it was looming in the distance out there. In my imagination, somehow the river turned into a concrete-sided canal in the book, which is how I remember it, and there is a scene in the book where Jimmy Robbins is sliding toward that canal and is he going to fall in or not…well, again, I don’t want to ruin it for you, but that black water really does exist at Bonnie Briar and I’m still afraid of it, all these years later. As in the book, there is an outcropping of rock which you can sled off of and go in the air for about a five-foot drop. You land on the snow with a thud and continue on down the hill, and it’s actually quite exciting.

In addition to ice skating on the creek, in real life we also skated on the duck pond across town, the official name of which is Gardens Lake. Everybody knows it as the duck pond, however, and I have black-and-white photographs of my grandfather Leo Fish (a.k.a. Grappa) with his children (my mother Patience and her brother Kenneth), along with their mother Dorothy Fish, skating on the duck pond in the 1930s. Mom took us kids skating there when we were small children and we never stopped skating at the duck pond all through high school. Well, when I chose to have a pivotal scene of conflict between Adam and Billy Collins (because of Sally, of course), I set the scene at the duck pond during an ice-skating session. I never saw any conflict at the duck pond during my childhood, but it was fun to set a fight scene on the ice there in my novel.

In the winter, you have plenty of time to spend indoors, and my father used to make balsawood models of World War I airplanes, such as the Sopwith Camel. I helped him make these models, with all of the tiny, thin wood pieces that had to be glued together in a painstaking fashion, and I hovered over every drop of glue that Dad placed on these wood pieces. I loved to watch him press each piece of wood against the next one and wait for the glue to harden and then he would stick these pieces of wood into other sections, slowly but surely making the fuselage come into view, then the wings and the tail. After the frame was made, we covered the plane with tissue paper, which we later painted and bedecked with decals. (I later made plastic models of my favorite cars, such as the 1964 Corvette Stingray)

I still have a special place in my heart for the many hours that Dad and I spent making these balsawood airplanes when I was a kid, so when it came time to giving Jimmy Robbins a character trait in my novel, I made him a master Sopwith Camel balsawood model maker, and I had a number of these model airplanes hanging from the ceiling of his bedroom, showing that even though he was dyslexic, he was actually a very smart kid who could follow complicated directions to make a thing of beauty, something that my main character Adam could not imagine himself capable of doing. This, of course, is true of many dyslexic people, that they become accomplished scientists, artists, and businessmen. It’s just that they have trouble with reading as quickly as other kids in school, and so in the past were labeled as slow learners when in reality they often have brilliant minds if given half a chance to show it. So in these model-building scenes, I was able to remember Dad fondly, and make a statement about learning disabilities as well.

Another character in the book was thinly based on a childhood friend who was the son of the minister of our local church, and although I made the fictional character a prejudiced bully, the real person was nothing of the sort. Fortunately, the fictional character, Bobby Taylor, is redeemed by the end of the book. The Larchmont Avenue Church (called the Beachmont Congregational Church in the novel) is still there in the center of town, and the Catholic church down in the Larchmont Manor, St. John’s, is still there as well. It sits facing the beautiful Fountain Square with a famous fountain in the middle of it. This is where Sally and Adam have their meeting on Halloween when Sally’s older brother Peter calls Adam a “Jew.” Although Adam eventually attends services in the Catholic church, which I call St. Catherine’s, I never set foot in this church in real life, even though it was only a few blocks from my house.

Speaking of not setting foot in religious houses of worship, I never attended temple when I was a kid. In fact, I never went to religious school, and I was never bar mitzvahed. My parents believed that God was everywhere and that you didn’t have to show that you believed in him by attending a formal service every week or by belonging to a church or temple. We had two temples in the Larchmont—Larchmont Temple on Larchmont Avenue; and Beth Emeth Synagogue on the corner of Larchmont Avenue and the Boston Post Road. I never went into Beth Emeth, and I think I went into Larchmont Temple a couple of times, so how did I come to write about bar mitzvahs and things like that in this book? To be honest, I don’t know. It just happened. First the kids meet Martin Luther King, and then I just figured that Adam would want to do a mitzvah that was related to Dr. King, for his own bar mitzvah. I’m not sure where the idea for a bar mitzvah came from.

At first, Adam rebels about having to study Hebrew and have a bar mitzvah, but his father, a Holocaust survivor, tells him that all he has to do is the bar mitzvah, then he never has to set foot in a temple again. Even so, Adam doesn’t want to go through with it, but after meeting Dr. King, he finds a higher purpose and decides to dedicate his bar mitzvah to Dr. King and his message of peace and understanding. In order to write the bar mitzvah scene, I had to do some research, and thanks to the Internet, I watched a number of bar mitzvah videos in their entirety and I wrote up the ceremony based on what I saw. I think I’ve only been to one bar mitzvah in my life, so my experience with this aspect of Jewish life is severely limited. Nevertheless, I think I got it right, as they say.

But where did Adam’s father, the Holocaust survivor, come from? Well, a close friend of mine from college had a father who had escaped from the train that was taking him to a concentration camp during the War. My friend’s father eventually settled in New York and started a business repairing luggage, and that was what put my friend through college. Adam’s last name is similar to my friend’s last name, in fact, so I pay tribute to my friend’s father twice in the novel. I made up all the details about the dry cleaning business and Mr. Jacobs’ uncle who took him under his wing, but I think it works well in the book as this would be a fringe occupation that would keep Adam’s father on the periphery of the social network in Beachmont, that is, until he is discovered by the community—but you’ll have to read the book to see how this happens.

One aspect of THE MARTIN LUTHER KING MITZVAH that I’m particularly fond of is the music. I don’t know why novels do not mention the music that the characters listen to, but I was not going to let this opportunity get past me. I will mention some of the songs that Adam heard, in chronological order, as they appear in the book, and make a few comments about them. Remember, these songs would have been heard primarily over the AM radio, namely WABC-AM in New York. Who can forget the first time they heard “Walk Away Renee” by The Left Banke, one of the prettiest songs ever recorded. I use this as a reference to the possibility that Sally will walk away from Adam someday, a thought that he abhors; then there’s “I’m A Believer” by the Monkees, and in real life, I remember our dance instructor playing this song on his record player during our dance classes (which he also does in the novel), and I must have been in love with some girl at that time because I remember being a believer in that infatuation, but in the novel, I transpose this feeling to Adam’s love for Sally and the way this song just inspires him to love her all the more.

Now, when I was a kid, we had all of the Peter, Paul and Mary records in our TV room, which also had a record player in it, and I played the grooves out of all of these records and sang along to them. On one of the record album covers, I actually wrote in the words “and Matt” after the Peter, Paul and Mary names, as if I were a member of the group. Silly, but cute. That’s how much I loved Peter, Paul and Mary. So in the novel, making a reference to Peter, Paul and Mary’s version of Pete Seeger’s classic “Where Have All The Flowers Gone,” especially since Adam and Sally meet Seeger, was a no-brainer, but it was also exactly how I felt when I was a kid. I just listened to Peter, Paul and Mary all the time. At one point, Gladys McKinley tells the kids she has an advance copy of Peter, Paul and Mary’s newest album, and I mention that there is a song about a jet plane. Of course, this is “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” but I chose to make a vague reference to it rather than name the song itself. After all, everybody knows which song this is.

Speaking of Pete Seeger, I went to a Seeger concert at, I believe, New York University when I was about sixteen. It was in a small music room and there couldn’t have been more than one hundred people there. Seeger played for well over an hour, I’d say, and it was a remarkable experience, because I could see this icon in his fishnet sweater, strumming on the banjo and playing with all of his heart, and I thought, again, if that’s what being an artist is in this country, I’d like to be one of those guys. So the opportunity to bring Pete Seeger into THE MARTIN LUTHER KING MITZVAH as a character was too good to pass up, and I hope I did justice to his memory. By the way, the song “The Big Muddy” was such a controversy at that time that I had to write it into the book, and I’m hopeful that this metaphor for the Vietnam War will resonate with kids today and that they wise up to the dangers of a president who will continue to wade through a swamp of destruction and refuse to change course. Unlike Adam, I never did meet Pete Seeger, but I wish that I had.

Now as I said, most of the music that Adam heard came over his transistor radio (which he carries around in the book), and in real life, I had a transistor radio as a kid and I listened to all of the AM hits, even late at night under the covers of my bed. But in the 1960s, there was one New York disc jockey who dominated the airwaves, and that was Bruce Morrow, better known as Cousin Brucie. As it happens, Cousin Brucie actually lived in Larchmont for a time, I think near the duck pond, across from a big waterfall where the Sheldrake River flows into the pond.

In my book, I created a character called Cousin Louie, and he also lives near the duck pond and he takes Adam and Sally under his wing and puts them on WABC-AM after they launch their protest against the Vietnam War in Beachmont. I think it’s a charming incident where the soundtrack of the book interfaces with the DJ who is bringing the music to these kids over the radio. Had the real Cousin Brucie not lived in Larchmont, I probably would not have come up with this idea.

But back to the music, who could forget “Happy Together” by the Turtles. If ever a young kid were in love, listening to “Happy Together” over the radio would seal the deal in his or her heart. Of course, I couldn’t resist making a little dig in the book at the song “Somethin’ Stupid” by Nancy Sinatra and Frank Sinatra. That song seemed to be on the radio forever, and I remember it even got on my nerves when I was in the seventh grade. Now, I couldn’t resist making a tribute to Motown, so Adam listens to “Bernadette” by the Four Tops; “Jimmy Mack” by Martha and the Vandellas; and “Respect” by Aretha Franklin, not to mention “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley, and all of this great music made up for the Sinatras. Another classic tune that I had to mention in the book was “Groovin’,” by the Young Rascals. In fact, I make three references to it. I really think 1966 to 1967 was the best music ever on AM radio, and I was lucky as a kid to have listened to it all and fortunate as an adult to be able to mention these great songs in THE MARTIN LUTHER KING MITZVAH.

As I mentioned at the beginning, when I was a kid I went down to Manor Park and imagined that the rocks on the shoreline became different things. I did this with my sister, and we actually started on a high plateau of rocks, which was the beginning of the toaster, then hopped down into the crevasse where the bottom of the toaster was, then climbed back up out of the toaster, burned to a crisp. We saw the whale nearby, a large, horizontal rent in the rock ribbons which became the mouth of the whale, the undulating rocks going back becoming its body, and even a tail at the end. All of this was quite clear to us, including a solitary boulder that became the pig, even though it didn’t have a head or a tail. I use all of these images in the novel, only instead of my sister and myself, I had Adam and Sally pretending the rock formations are these things. It was fun to write about my childhood memories at Manor Park in this way.

Speaking of Manor Park, the gazebos in the park are famous landmarks, and I couldn’t write about Larchmont, that is, Beachmont, without writing about the gazebos. There is a north gazebo and a south gazebo, as well as umbrella point, where a large umbrella is strapped to the rocks. It is in the north gazebo that Adam and Sally have their first kiss, as Sally tells Adam to turn off his transistor radio that is playing “Groovin’” at the time. What a glorious place for these two kids to share a tender moment, looking out at the Long Island Sound as the wind blows through their hair on a beautiful spring day and the gulls cry out in the distance.

I don’t know if everyone feels the same way about their hometown as I feel about Larchmont. Of course, I am covering up a lot of the bad stuff. There’s competition in suburban New York towns, with the parents for the available jobs in the city; with the kids, who is going to measure up and do better than everybody else? As the song says, if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere. I choose to remember the beauty and dignity of basically growing up in a small town, even though the community was intimately connected with New York City. Maybe, in a way, by writing this book about Larchmont, I have made it the way you’re supposed to do when you come from a place like that. I certainly hope so.

© Copyright 2018 Mathew Tekulsky